Publications Featuring Dr. Langsdon

Dr. Langsdon awarded as a 2025 reviewer for Aesthetic Surgery Journal Open Forum

Dr. Langsdon gives a candid interview to Modern Aesthetics about Covid-19 and the effect it has had on him personally and on elective healthcare in general.

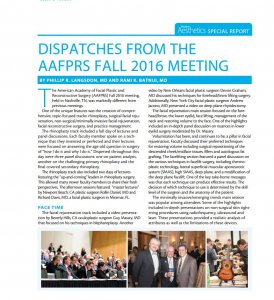

Dr. Langsdon featured in research article discussing the submental medialization and suspension procedure

Langsdon, PR, Petersen, D. Management of the Aging Forehead and Brow: Facial

Plast Surg. Submitted Sept. 2013. Theime Medical Publishers, New York. Accepted and Forthcoming.

Lingeman, R., Langsdon, P, Shellhammer, R.: Benign Tumors of the Nasopharynx-Angiofibroma, IN: Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, edited by Cummings, Fredrickson, Krause, Schuller, C.V. Mosby Co., 1986; 1269-1279. (book chapter)

McCollough, E., Gilbert, S., Langsdon, P.: The Difficult Nasal Tip, IN: Current Therapy in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, edited by Gates, G., B.C. Decker Co., 1986; 118-123. (book chapter)

McCollough, E., Langsdon, P.: Maskless Chemical Face Peel, IN: Dermatologic Clinics, edited by Ratz, J. L., Wheeland, R. G., Balin, R. L., W. B. Saunders Co., 1987; 381-392. (book chapter)

McCollough, E., Langsdon, P.: Chemical Peel & Dermabrasion, Thieme Medical Publishers, New York, New York, November, 1988 (textbook)

McCollough, E., Langsdon. P.: Chemical Face Peeling, IN: Dermabrasion and Chemical Peel, edited by Burks/Farber, 1986 (book chapter)

McCollough, E, Langsdon. P.: Chemical Peeling With Phenol, IN: Principles of Dermatologic Surgery, edited by Roenigk and Roenigk; Dekker, Co., 1988; 997-1016. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P., McCollough, E.: Chemical Peeling With Phenol, IN: Principles of Dermatologic Surgery, 2nd Edition, Roenigk and Roenigk; Dekker, Co., 1994 (book chapter)

McCollough, E., Perkins, S., Langsdon, P.: SAMAS Suspension Rhytidectomy Rationale and Long Term Experience, Archives of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 1989; 115:228-232

(journal article)

McCollough. E., Langsdon, P., Gilbert: External Rhinoplasty, Indian Journal of Otolaryngology, edited by Gosavi, D. K., 1986 (journal article)

McCollough, E., Langsdon. P., Gilbert: Facial Implants, Indian Journal of Otolaryngology, edited by Gosavi, D. K., 1986 (journal article)

McCollough, E., Langsdon, P., Gilbert, S.: Nasal Fractures, Indian Journal of Otolaryngology edited by Gosavi, D. K., 1986 (journal article)

Langsdon, P. R.: Phenol Peeling in: Facial Plastic Surgery; J. M. Willett, Editor; Stamford, CT, Appleton-Lange, 1997; 207-214. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P. R.: Tennessee-A Political History; Franklin, Tennessee, Providence House Publishers, 2000 (textbook)

Langsdon, P., Milburn, M., Yarber, R.: The Comparison of Laser & Chemical Peel In Facial Skin Resurfacing, Archives of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2000, 126:1195-1199. (journal article)

Langsdon, P.R.; Chen, D.K.: Comparison of The Laser and Phenol Chemical Peel In Facial Skin Resurfacing, Current Medical Literature, 2002, 3:49-52.

Langsdon, P.R.: Hipopigmentacion A Largo Plazo: comparacion entre la exfoliacion con laser y la quimica, Int J Cosm Med Surg 2005:7(2):38-43. (Publisher: Acindes, Buenos Aires, Argentina)

Langsdon, P., Knipe, T., Whatley, S, Costello, T.: Transconjunctival Approach to the Zygomatico-Frontal Limb of Orbitozygomatic Complex Fractures, Facial Plastic Surgery, Thieme Medical Publishers, New York, Volume 21, Number 3, 171-175. 2005.

Langsdon, P.R.: Nasal Tip Rotation in: Simplified Facial Rejuvenation; Shiffman, M., Mirrafati, S., Lam, S., Cueteaux, C., Editors. Springer Verlag, Berlin. 2008. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P.R.: Comparision of Laser and Chemical Peel in: Simplified Facial Rejuvenation; Shiffman, M., Mirrafati, S., Lam, S., Cueteaux, C., Editors. Springer Verlag, Berlin. 2008. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P.R.: Mini Facelift in: Simplified Facial Rejuvenation; Shiffman, M., Mirrafati, S., Lam, S., Cueteaux, C., Editors. Springer Verlag, Berlin. 2008. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P., Metzinger, S., Glickstein, J., Armstrong, D.:Transblepharoplasty Brow Suspension, An Expanded Role, Annals of Plastic Surgery. Vol. 60. Number 1, Jan. 2008

• Transblepharoplasty Brow Suspension: An Expanded Role

• Comparison of the Laser and Phenol Chemical Peel in Facial Skin Resurfacing

Langsdon P.R., Gorman, M.: Deciding whom to perform a procedure on, which procedure and how to say ‘no’, in Carniol PJ and Monheit G (eds), Aesthetic Rejuvenation in Clinical Practice: Informa Healthcare, London 2010. (book chapter)

Langsdon, P.R., Rohman, G.T., Hixon, R., Stumpe, M.R., Metzinger, S.E.: Upper Lid Transconjunctival vs Transcutaneous Approach for Fracture Repair of the Lateral Orbital Rim, Annals of Plastic Surgery. Vol 65, Number 1, July 2010

Langsdon PR, Watkins JP, McCollough EG: Phenol Chemical Peels. Goldenberg/Goldstein, Handbook of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Thieme Medical Publishers, NY 2010

Langsdon, P.R., Williams, G.B., Rajan, M.D., Metzinger, S.E.: Transblepharoplasty Brow Suspension Using a Biodegradable Fixation Device, Aesthetic Surgery Journal November/December 2010 30:808-809

Langsdon, P.R., Shires, C.: Modified Facelift ; In Cosmetic Surgery: Art and Techniques, MA Shiffman, A Di Giuseppe (eds), pps 329-335 Springer Heidelberg NewYork, Dordrecht London, 2013

Langsdon, P.R., Shires, C.: Facelift ; In Cosmetic Surgery: Art and Techniques, MA Shiffman, A Di Giuseppe (eds), pps 311-322 Springer Heidelberg NewYork, Dordrecht London, 2013

Langsdon, P.R., Rodwell, D. W., Velargo, P.A., Langsdon, C. H., Guydon, A.: Latest Chemical Peel Innovations; Emerging Tools and Trends in Facial Plastic Surgery, Thieme Medical Publishers, NY; May 2012, Vol. 20, No. 2. pps 119-123

Langsdon, P.R., Shires, C., Gerth, D.: Lower Face Lift with Extensive Neck Re-Countouring; Facial Plast Surg 2012;28:89-101, Thieme Medical Publishers, New York

Langsdon, P.R., Shires, C.: Chemical Face Peeling; Facial Plast Surg 2012;28:116-125, Thieme Medical Publishers, New York

Langsdon, P.R.: Preface, Management of the Lower Third of the Face and Neck: Facial Plast Surg 2012;28:1-2 Thieme Medical Publishers, New York

Langsdon, P.R., Velargo, P.: Upper Face Rejuvenation, in Debate on Current Topics in Facial Plastic Surgery, (ed) Kellman, R. & Fedok, F. in Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 20 , Elsevier Inc. New York, submitted November 2011, Accepted and forthcoming.

Langsdon, P.R., Velargo, P.: Surgical Manipulation of the Periorbital Musculature: Multidisciplinary Insights, (ed) Nahai, F. Clinics In Plastic Surgery Vol 40,(1): 125-131, January 2013, Elsevier, New York

Langsdon PR, Rodwell DW, Velargo PA, et. al. Latest Chemical Peel Innovations. In: Emerging Tools and Trends in Facial Plastic Surgery. Carniol PJ, ed. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2012 May; 20 (2): 119-23.

Langsdon PR, Velargo PA, Rodwell DW. Latest Chemical Peel Innovations: The Enhanced Superficial Chemical Peel. Haut. 2012 October; Heft 5, Band XXIII: 205-6.

Langsdon PR, Rodwell DW, Velargo PA, et. al. Superficial Chemical Peels. In: Minimally Invasive Office Based Procedures in Facial Plastic Surgery. Fedok FG and Carniol PJ, editors. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers. 2014. pp 43-46.

Langsdon PR, Rodwell DW, Velargo PA. Submental Suspension Platysmaplasty. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. Vol. 33, No. 7, Sept. 2013, p 953-966.

Langsdon PR, Petersen D. Complications of Chemexfoliation in “Lasers and Light, Peels and Abrasions for Health, Beauty and Disease”. Submitted March 2014. Theime Medical Publishers, New York. Accepted and forthcoming in January, 2015.

Langsdon PR, Petersen D. Medium Depth Chemical Peel in “Lasers and Light, Peels and Abrasions for Health, Beauty and Disease”. Submitted March 2014. Theime Medical Publishers, New York. Accepted and forthcoming in January, 2015.

Transblepharoplasty Brow Suspension An Expanded Role

Phillip R. Langsdon, MD, FACS,*† Stephen E. Metzinger, MD, FACS,*‡ Jonathan S. Glickstein, MD,† and David L. Armstrong, MD†

Abstract: Brow position and hyperfunction of the muscles of forehead facial expression contribute to the aging diathesis of the upper one third of the face. In many cases, the eyelids and brows are addressed together to achieve a satisfying rejuvenation effect. Many different approaches to the brow are used, including the long coronal or pretricheal incisions, direct incision of the suprabrow or forehead, and finally the use of smaller incisions with an endoscopic technique. Another technique, deserving of further consideration, is the transblepharoplasty brow lift (TBBL). Though generally reserved for occasional use, this technique is easy to perform, minimizes facial incisions and operative time, and can achieve results comparable to other, more extensive, approaches.

Key Words: forehead aesthetics, browlift, blepharoplasty (Ann Plast Surg 2008;60: 2–5)

Brow ptosis may result from the combined effects of increased skin laxity and the relative hyperfunction of the depressors of the brow. The corrugator supercilii, depressor supercilii, procerus, and orbicularis oculi muscles all play a role in lowering the position of the brow.1,2 Surgical approaches to lift the brow include coronal, pretricheal, trichophytic, direct, temporal, midforehead incisions, and minimal incision endoscopic techniques. Each of these approaches has specific advantages and disadvantages, and, while there are indications for all, they involve additional incisions or the use of additional, costly equipment. These are important considerations for both the patient and surgeon. The transblepharoplasty brow lift (TBBL) minimizes patient morbidity, additional incisions, and equipment cost by utilizing the blepharoplasty incision while simultaneously providing direct access to the tissues being addressed. Direct placement of suspension sutures or supporting implants at the site of ptosis is at least as effective as distant support techniques. There is little limitation with this approach, other than the ability to excise forehead skin or hair-bearing scalp.

Technique

After a standard upper-eyelid blepharoplasty approach is performed, a suborbicularis muscle flap is raised in the lateral two thirds of the eyelid until the orbital rim is reached. The subgaleal plane is entered immediately at the superior orbital rim. Critical to the technique is dissection in the subgaleal plane, thereby protecting the skin, creating a glide plane external to the pericranium while simultaneously leaving the pericranium as a deep attachment point to aid in suspension suture placement. Once the lateral pocket is developed, adequate elevation can be carried out to all areas of the lateral forehead through the blepharoplasty incision. The forehead is broadly undermined from the lateral orbital rim inferiorly to the hairline superiorly. The dissection is carried out from the temporal line laterally to the midforehead medially. Rarely, dissection can be carried out to a more lateral extent through the temporal line, should the surgeon determine that more forehead mobility is needed.

The orbicularis oculi can be divided at the lateral one-third point of the blepharoplasty incision. This is accomplished with careful bipolar cautery, followed by scissor dissection. The muscle is usually very thin, and the division should stop as the thin subcutaneous tissue is encountered. If the preoperative brow position is high laterally, we do not divide the orbicularis muscle.

The medial portion of the eyelid incision is addressed next. Suborbicularis dissection is carried out with a scissorspreading technique until the medial depressor muscles are encountered. The medial depressor muscles of the brow can be easily visualized and divided using cautery and scissors.

The medial depressor muscles are thicker than the lateral orbicularis and have a more abundant blood supply. Therefore, the muscles are divided in a progressive incremental fashion until complete muscular division is obtained. The corrugator and depressor supercilii muscles are the first encountered in the medial dissection. Once they are divided, the scissor-spreading is continued medially until the procerus muscle is encountered. This muscle can be easily divided using the incremental cautery and division technique. If the preoperative brow position is high medially, we do not divide the corrugator muscles. Full access to both the medial and lateral depressor muscles may be obtained with minimal risk to the critical neurovascular bundles. Bleeding points of the entire forehead are readily identified under direct vision and controlled with a guarded bipolar cautery.

Suspension sutures are placed utilizing a 5-0 nylon or polydioxanone through the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle into the periosteum of the suprabrow region (Fig. 5A, B). An implantable absorbable anchor of L-polylactic acid may also be used to support the brow during the first few months of healing. Despite suspension, defining the degree of final brow elevation to a particular location is not possible as the tissue planes begin to slide. After support has been placed, the eyelid skin is closed using 6-0 fast absorbing plain gut.

Postoperative care is similar to other brow and forehead procedures. A light pressure dressing may be applied for 24 hours. Cool compresses are used to minimize eyelid swelling. Micropore tape is occasionally used to suspend the suprabrow region to the upper forehead tissues. The patient is instructed to elevate the head at rest for 2 weeks.

Outcomes

In 225 cases over 13 years, we report no major complications. However, uneven brow position, sensory nerve injuries, hematoma, loss of suspension suture in the early postoperative period, and frontal nerve paralysis are all possible. Moreover, it is not unusual to experience some transient puckering of the brow due to the suture fixation in the perioperative period.

Swelling occurs with any surgery; however, there is usually more swelling in the eyelid region with the TBBL than when eyelid surgery is undertaken without forehead surgery due to the fact that elevated forehead flap is open only to the gravity-dependant eyelid incision.

In general hematoma formation is rare in patients without a history of abnormal bleeding and with normal coagulation studies who also avoid anticoagulant medications, herbs, and vitamins for 2 weeks before and 1 week following surgery. In the rare cases in which the field is not completely dry in spite of the best efforts with bipolar cautery, a small drain site may be created behind the hairline and a small Penrose drain can be placed until the following day. We have never encountered a forehead or eyelid hematoma requiring drainage in our series of TBBL patients.

Hypesthesia is normal and usually temporary. We have not had any complaints of serious hypesthesia with this technique. Frontal nerve weakness can occur as with any brow or forehead procedure in which there is stretching, pulling, or cautery in the suprabrow tissues. We have not encountered any cases of frontal paralysis with this technique.

There are asymmetries in every face, and there are usually some differences between the brows. This should be pointed out to the patient before surgery is done because perfect symmetry is not a realistic goal of any facial esthetic technique. Although we have not encountered any situations where an obvious worsening of asymmetry occurred in any of our patients, taping of the suprabrow skin to the upper forehead may help prevent loss of suture fixation during the early healing process.

Of the 225 patients treated over 13 years, only 1 patient required reoperation. This patient had severe forehead redundancy. Although the brows were significantly elevated over the presurgical state, additional improvement was obtained through a pretricheal forehead lift.

The short- and long-term results of this approach are excellent and are comparable to other techniques.

DISCUSSION

There is little discussion of the TBBL in the literature. Since Sokol and Sokol3 described the technique in 1982, only 2 other articles have been published concerning it. Certain criteria have been proposed to suggest when TBBL is most appropriate (Table 1).4,5

While these factors are useful guides, the indications should be broadened due to the minimal invasiveness, ease, and effectiveness of the technique. TBBL ought to be considered whenever a traditional brow lift is indicated.

There are many other effective approaches for addressing ptotic brows, which are commonly performed in conjunction with upper-eyelid surgery, and, in fact, we perform all techniques available when it is felt they are indicated. However, traditional brow-lifting techniques involve 1 or more additional incisions in the brow or scalp to access the ptotic areas of concern and the depressor muscles. Occasionally these larger incisions are replaced by smaller ones in tandem with an endoscope to assist visualization. While effectiveness is always the greatest concern in cosmetic surgery, morbidity and cost must also be considered. TBBL has the advantage of utilizing existing incisions without the need for additional equipment.

Gravity, excess tissue, and the inferior pull of the depressor muscles or the inaction of the frontalis muscles are responsible for brow droop. The transblepharoplasty brow lift addresses the inferior displacement of tissue via full frontal forehead elevation. However, in most cases depressor muscle division is necessary to allow a superior movement of the brow tissues. Although the divided depressor muscles tend to regain some function, they are usually weakened enough to diminish active depression. The authors do not currently employ excision of the depressor muscles, because this technique may result in an area of skin depression.

Distant approaches to the brows, such as the endoscopic technique, also use the advantage of muscular division to allow an upward drift of the brows. Our current TBBL technique also includes division of the lateral orbicularis muscle in most cases. It is the belief of the authors that depressor muscle division is a key in brow elevation. Without division of the depressor muscles, there is a continued downward pull that opposes any surgical efforts to elevate the brows. There are certain situations where we alter our muscle- division approach. Patients presenting with high and widely divergent medial brows may not need medial depressor muscle division. Likewise, patients with high lateral brows may not need lateral orbicularis division. Muscle division is planned according to the anatomy present.

Utilizing the TBBL permits the surgeon to suspend the ptotic brow directly to the suprabrow region. Suspension sutures are placed at the area of concern and can be adapted to address degree and location of tissue ptosis. This is in stark contrast to traditional endoscopic approaches where elevation is in the subperiosteal plane and regional brow tissues are remotely elevated unnecessarily en masse. By securing only lax brow tissue at the areas of ptosis to densely adherent periosteum, tension on the suspension sutures is minimized. TBBL provides optimal utilization of existing incisions, avoiding additional incisions. We believe anchoring aids in providing some time for the brow to adapt to a relative elevated location. But fixation is usually only partial because of the multiple layers of the forehead tissue. All forehead/ brow elevation techniques suffer from some limitation of elevation because of the multiple layered nature of the forehead and the gliding of these layers over the periosteum. The inability to obtain total fixation of the multiple forehead layers is likely the reason we have not observed any longterm restriction of brow movement after the placement of temporary or permanent sutures.

Extensive tissue mobilization can also be obtained through the TBBL without elevating the hairline. Hairline elevation is seen with many endoscopic and coronal incisions. Coronal incisions placed anterior to or within the frontal hairline, of course, may actually lower the hairline, but at the expense of a long incision. Forehead elevation from the eyelid incision accomplishes the same detachment advantages as with incisions in the frontal hairline area. However, partial or complete hairline incision techniques with supporting sutures or implants in a position distant to the brow must overcome the physics of tissue stretching over the distance from the suspension suture or implant to the brow, as well as the increased weight of support of the entire forehead. The transblepharoplasty support is at the brow and does not face the same tissue relaxation or weight issues as the more distant techniques. The brow is more easily mobilized with this more direct approach.

CONCLUSION

In many practices, TBBL receives little consideration, whereas traditional techniques are used more frequently. It is the opinion of the senior authors that TBBL should be more commonly applied as it provides excellent results while reducing the number of incisions and the need for additional equipment, providing direct access, extensive mobilization, and suspension to the site of ptosis. Moreover, in our hands transblepharoplasty approach to treatment of the ptotic brow is as effective as the endoscopic approach, with rare complication.

REFERENCES

1. Knize DM. Muscles that act on glabellar skin: a closer look. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:350 –361.

2. Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1321–1333.

3. Sokol AB, Sokol TP. Transblepharoplasty brow suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:940 –944.

4. Ramirez OM. Transblepharoplasty forehead lift and upper face rejuvenation. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:577–584.

5. Paul MD. Subperiosteal transblepharoplasty forehead lift. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20:129 –134.

Annals of Plastic Surgery • Volume 60, Number 1, January 2008

Received October 30, 2006, and accepted for publication, after revision, January 28, 2007.

From the *Langsdon Clinic, Germantown, TN; *Division of Facial Plastic Surgery, †Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of Tennessee, Health Science Center, Memphis, TN; and ‡Aesthetic Surgical Associates, Metairie, LA. No economic support derived in preparation of this manuscript. Reprints: Jonathan S. Glickstein, MD, 956 Court Ave, Suite B226, Memphis, TN 38163. E-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © 2007 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

ISSN: 0148-7043/08/6001-0002

DOI: 10.1097/01.sap.0000261536.38116.2c

Comparison of the Laser and Phenol Chemical Peel in Facial Skin Resurfacing Phillip R. Langsdon, MD; Mark Milburn, MD; Robert Yarber, MD

Objective: To determine differences in postoperative outcomes, complications, and adverse effects between phenol chemical peel (CP) and the carbon dioxide laser peel, when used for facial skin resurfacing.

Design: Nonrandomized prospective comparison of 2 facial skin resurfacing techniques using a split-face paradigm. In this initial study, 18 months of follow-up data are available, including the patients’ subjective evaluations, the surgeons’ objective assessments, and a histological analysis of 1 patient by a blinded pathologist.

Setting: A facial plastic surgery clinic associated with a university medical center.

Patients: Four female patients with actinic-damaged facial skin and facial rhytids, aged 61 to 73 years.

Interventions: The left side of each face was treated with a phenol-based CP formula according to standard procedure. The right side was resurfaced using the Sharplan Silktouch Flashscanner carbon dioxide laser. Patients were photographed before treatment and at regular intervals postoperatively. One patient underwent rhytidectomy at 2 months posttreatment, and specimens were obtained for histological analysis.

Main Outcome Measures: Evaluation of observable clinical improvement in skin quality, postoperative swelling, erythema, pigmentary alterations, healing time, and complications.

Results: All 4 patients experienced transient initial discomfort on the CP side that subsided within 24 hours after treatment. The laser side was noted to have slightly more prolonged stinging, erythema, and edema. Erythema was noted to be more uniform in the lasertreated areas. Final clinical improvement in rhytids was evaluated by 4 surgeons who reviewed color slide presentations of each patient 1 year or more postoperatively. Uniform wrinkle improvement was noted around the eyelid and lateral cheek areas on both the CP and lasertreated sides. A moderate advantage in the degree of wrinkle improvement was noted on the laser-treated sides of the upper lip and forehead. Thick-skinned, glandular skin areas, such as the nasolabial fold and chin, were found to be substantially smoother in the laser-treated areas. Histological studies indicate that the CP side was noted to have a deeper injury, extending into the reticular dermis. The skin treated with the laser was injured more superficially, down to the papillary dermis.

Conclusions: Phenol CP is as effective as the laser in diminishing rhytids in the thin-skinned areas of the face. The laser produces improved results in the thick, glandular areas of the face, but also produces more intense hypopigmentation, longer periods of patient discomfort, and longer periods of postoperative erythema. Both phenol CP and laser resurfacing remain useful clinical tools.

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1195-1199

FOR MANY years, dermabrasion and chemical peel (CP) have been available as methods of skin resurfacing for fine facial rhytids. The relative merits of each technique have been the subject of lively debates. With the recent advent of carbon dioxide laser skin resurfacing techniques, a new element has been added to the debate. Histological studies have demonstrated that high-energy, short-pulse carbon dioxide lasers produce an injury similar to but shallower than that produced by a deep CP.1 To date, no prospective clinical trials comparing lasers with CPs with respect to postoperative course, patient satisfaction, histological examination, and long-term outcome have been performed.

At our institution, patients with fine facial rhytids and sun-damaged skin have routinely received deep chemical exfoliation using a concentrated mixture of phenol, croton oil, Septisol antimicrobial soap (Calgon Vestal Laboratories, St Louis, Mo), and distilled water without an occlusive dressing. Until recently, laser techniques were limited by small spot size and cumbersome, bulky equipment. With the development of small, computer-controlled laser handpieces, full-face laser skin resurfacing has become a practical option. Unfortunately, there are no data available that support the advantage of either the laser or chemical exfoliation in the improvement of fine facial rhytids. In order to highlight important differences between the 2 techniques, we present data on 4 patients in whom the laser was used to treat the right side of the face and CP was used to treat the left side of the face.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The research protocol was approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board. Four female patients with photodamaged skin and facial rhytids were entered into the study. None of the patients had prior skin resurfacing procedures or face surgery related to aging. Potential risks and benefits were discussed with all patients and informed consent was obtained. Patients were photographed preoperatively and postoperatively using a Lester Dine 105 macro lens camera system (Lester A. Dine Inc, Palm Beach Gardens, Fla) at an f-stop ratio of 1.2:16 for full face frontal, oblique, and lateral shots. A 0.7:22 setting was used for close-up periorbital, perioral, and forehead views.

Prior to surgery, the patients’ skin was cleansed 3 times with Septisol antimicrobial soap. Oral sedation was administered using 20 mg of diazepam and 200 mg of dramamine. During surgery, patients received intravenous 5% glucose solution in lactated Ringer solution at 200 mL/h, and were monitored continuously by electrocardiogram and pulse oximetry. Field blocks were performed with 1% lidocaine. The patients’ faces were then degreased with a 22322 gauze pad containing acetone. The left side of each patient’s face was treated with a phenolbased CP solution containing 3 mL of phenol, 3 qt of Croton oil, 8 qt of Septisol soap, and 2 mL of distilled water. The peels were then applied according to standard procedure.2 Following the peel, the right side of the face was treated with the Sharplan Silktouch Flashscanner carbon dioxide laser (Sharplan Laser Co, Tel Aviv, Israel). Spot size/power setting/ exposure times of 3 mm/6W/0.2 seconds (periorbital region) and 6 mm/16 W/0.2 seconds (forehead, cheek, chin, and perioral regions) were used for each patient. Debris was wiped from the skin with sterile gauze and a second pass was performed for the laser-treated areas using the same power settings.

Patients were instructed to gently shower the face 6 times daily, beginning 24 hours after surgery. Each showering was followed by application of a moisturizing cream (Eucerin; Beiersdorf Inc, Norwalk, Conn). Patients were reevaluated at 24 hours postoperatively, followed by visits at increasing intervals over 3 months. Observations were made by the primary surgeon regarding swelling, erythema, pigmentary alteration, and cosmetic benefits of treatment. One patient (case 1) underwent rhytidectomy at 44 days posttreatment, and histological specimens were obtained from treated and untreated areas of both the laser-treated and CP sides of the face. Specimens were submitted for hematoxylin-eosin as well as elastin stains (Verhoeff elastic tissue stain) and evaluated by a blinded examiner (Edwin A. Raines, MD, Memphis, Tenn).

REPORT OF CASES

CASE 1

A 73-year-old white woman with moderate actinic skin damage and facial rhytids was treated using the split-face paradigm with a phenol peel on the left hemiface and laser skin resurfacing (Silktouch Flashscanner carbon dioxide laser) on the right. She received oral acyclovir (Zovirax; Glaxo Wellcome Inc, Research Triangle Park, NC) during the perioperative period because of a history of fever blisters, and topical acyclovir (Zovirax) was added on postoperative day 1 because of an early vesicular lesion. Postoperatively, the patient reported only sunburn-like discomfort on the CP side that resolved within the first 8 hours postoperatively.

The patient felt that the cream did not adhere well on the lasertreated side and adhered much better on the CP side. She was noted to have more uniform erythema on the laser-treated side with comparatively spotty erythema on the CP side. The patient also felt that the cleaning regimen was somewhat uncomfortable on the laser-treated side, while it was relatively comfortable (after the first 24 hours postoperatively) on the CP side. At 44 days posttreatment, she underwent rhytidectomy. At the time of surgery, her skin texture was noted to be smoother in the glandular areas of the laser-treated side (chin, nasolabial fold), with noticeably less effect on the sebaceous areas of the CP side. At the 3-month follow-up, the 2 sides were beginning to equilibrate, but a noticeable difference existed in the thicker, sebaceous areas. The laser-treated side had a uniform, slightly erythematous appearance, while the CP side showed less improvement on the thickskinned areas of the nasolabial fold and chin. The equilibration continued at 6 months. At 1 year postoperatively, 3 of 4 evaluating surgeons felt that the fine wrinkles over the thinskinned areas of the eyelid were equally improved by each method of treatment. Likewise, 3 of 4 felt that the thicker skin of the patient’s forehead and lips seemed to be uniformly improved bilaterally. All 4 agreed that the midcheek region had a better result on the laser-treated side. Three of 4 felt that the lateral cheek region fared better with the laser. Hypopigmentation was found to be worse by all 4 surgeons on the laser-treated side.

CASE 2

A 61-year-old white woman with significant rhytids and sun-damaged skin was treated per protocol using a deep phenol peel on the left hemiface and laser skin resurfacing on the right. She reported initial stinging on the CP side that subsided the evening of surgery (within the first 8 hours postoperatively). She noted some difficulty in keeping cream on the laser-treated side. At 2 weeks, she had more uniform erythema on the laser-treated side, with a slightly splotchy appearance on the CP side. At 1 month, the patient reported that the skin on the laser-treated side “felt tighter.” At 2 months posttreatment, she was noted to have mild hyperpigmentation on only the lasertreated side, which responded to treatment with 2.5% hydrocortisone cream and 4% hydroquinone. At the 3-month follow-up, the skin texture of the 2 sides was beginning to equilibrate, but a noticeable difference existed in the thicker, sebaceous areas. The laser-treated side possessed a uniform, slightly erythematous appearance, while the CP side demonstrated less rhytid improvement on the thick-skinned areas of the nasolabial fold and chin. Fine wrinkles over the thinskinned areas of the eyelids and lateral cheeks seemed to be uniformly improved bilaterally by the 3-month check. The upper lip and forehead began to show equivalent results by the 6-month posttreatment review. The nasolabial fold and chin continued to exhibit improved results on the laser-treated side, although much less so by the 6-month visit. At the 1-year posttreatment evaluation, 3 of 4 surgeons felt that the eyelid rhytids were equally improved with either technique. All 4 felt there was no advantage of either technique in the forehead. Two of 4 felt that the lateral cheek and midcheek appeared the same with either technique. Three of 4 favored the results of the laser in the treatment of the lips. Hypopigmentation was worse on the laser-treated side according to all surgeons.

CASE 3

A 67-year-old white woman with actinic- damaged skin and fine facial rhytids was treated per protocol using laser skin resurfacing on the right side of the face and a phenol peel on the left. On postoperative day 1, she denied having any pain on the peeled side but reported a stinging sensation on the laser-treated side especially when showering. After 1 week, the laser-treated side was uniformly more erythematous, and she complained of itching on this side only. She developed mild milia bilaterally on day 9. Stinging abated on the laser-treated side by 2 weeks postoperatively. Erythema of the laser-treated side persisted to the 1-month visit, but was resolved by the second month. At the 1-year evaluation, the forehead and eyelids appeared equally improved with either technique, with 1 surgeon favoring the CP side. Three of 4 surgeons favored the laser-treated side in the midcheek and lateral cheek areas. There was a division of opinion regarding the results in the lips; 2 of the 4 surgeons felt the results were equal, while 1 favored the CPtreated side and 1 felt that the lasertreated side was only slightly better. Three of 4 surgeons felt that the hypopigmentation was worse on the laser-treated side, with 2 considering the difference only minor. The fourth surgeon felt that the hypopigmentation was nearly equal.

CASE 4

A 68-year-old white woman with a history of actinic-damaged skin and prior skin cancer excisions was treated using the split-face protocol. The right hemiface was treated with laser resurfacing, and phenol peel was used to treat the left side. She reported more discomfort on the laser-treated side that subsided after 5 days. She denied experiencing any discomfort in the phenolpeeled areas. The laser-treated side was more uniformly erythematous, and erythema persisted to the 4-week follow-up appointment. Two of the 4 evaluating surgeons felt that the eyelids were equally improved with either technique, 1 favored the laser-treated side, and 1 favored the peel side; in other words, at least 3 of the 4 felt that the eyelids fared as well or better with the CP. Two of the 4 felt that the results were equal in the forehead; 2 favored the laser side. Three of the 4 favored the results of the laser in the lateral cheek and midcheek as well as the lips. All 4 felt that the hypopigmentation was worse on the laser-treated side.

RESULTS

Patients were seen at regular intervals postoperatively. The first 2 patients (cases 1 and 2) were followed up for 18 months postoperatively. The second 2 patients (cases 3 and 4) were followed up for 1 year. All were pleased with the overall improvement in skin quality and reduction of fine wrinkles, although patients could appreciate differences between the laser and chemically exfoliated sides. Most noted an advantage of the laser-treated side in improving the areas of the nasolabial fold and chin. By the operating surgeon’s evaluation, as well as the patient’s, there was near-uniform improvement in the eyelid and lateral cheek areas, while there was only a slight advantage with the laser in rhytid reduction in the upper lip and forehead. In areas of thicker, more glandular skin, such as the chin and nasolabial fold, the laser showed considerably more improvement early in the healing process. By 6 months, the laser advantage had diminished but was still present. Overall, the skin texture of the lasertreated side was more uniform in all patients compared with the somewhat patchy initial appearance of the chemically exfoliated skin. This is attributed in part to natural variability in oil content of the sebaceous areas despite vigorous degreasing with acetone and the variability of penetration of the chemical peel agents. This lack of uniformity in appearance diminished with time in the upper lip, forehead, periorbital, and lateral cheek areas.

Patients experienced relatively prolonged erythema of the laser- treated side. This side was also described as feeling tighter and being more sensitive. The increased sensitivity was still discernible by the patients 5 months posttreatment. Erythema and swelling on the CP side were patchy and less intense, with earlier resolution.

One patient began to develop increased pigmentation of the lasertreated skin 2 months posttreatment. She was treated with hydrocortisone and hydroquinone with a good response.

One patient underwent elective rhytidectomy 44 days postoperatively because of sagging in the cheek, jowl, and submental areas. Specimens from treated and untreated areas of both the lasertreated and CP sides were sent to a pathologist who had no knowledge of which technique was used. The injury was found to be deeper on the CP side, extending into the reticular dermis. The laser-treated tissue was injured more superficially, into the papillary dermis. Sun-damaged elastic connective tissue fibers were found to be obliterated by both techniques.

COMMENT

During World War I, Dr LaGasse of France noted that wounded skin treated with phenol and occlusive dressing healed with an improved cosmetic appearance. This idea was brought to America by his daughter Antoinette, who set up a “lay” peeling center for the improvement of scars and wrinkles.3 In subsequent years, CPs using phenol, trichloroacetic acid, and other agents were employed by a variety of non-medical “facial rejuvenation” centers with little attention from the medical community.4 Sir Harold Gillies began using carbolic acid in the mid-1950s as a treatment for laxity of periorbital skin.3 In 1966, T. J. Baker published his series of 250 patients treated with a phenol-croton oil peel and postpeel occlusive dressing, bringing CP into the mainstream of plastic surgery.5 His experience revealed that the phenol peel was best suited for fair, thinskinned white women with fine facial rhytids. He found that darker, olive-skinned individuals were prone to sharp demarcation lines and spotty hyperpigmentation.5

Today, a variety of agents, including phenol, trichloroacetic acid, resorcinol, glycolic acid, and salicylic acid, are used by cosmetic surgeons from a variety of specialties to effect a medium-depth chemical peel. Medium depth has been defined as wounding to the level of the upper reticular dermis, with a depth of 0.45 to 0.60 mm. Prior studies have demonstrated obliteration of damaged elastic fibers after mediumdepth CP with later neoelastogenesis. 6 Concentrated phenol has been found to have a keratocoagulant effect that produces injury into the mid-dermal region.7 The phenol peel (nonocclusive technique), using 3 mL of phenol, 3 qt of croton oil, 8 qt of Septisol, and 2 mL of distilled water, has been used in the practice of the senior author (P.R.L) for more than 16 years.

Recent advances have brought attention to the carbon dioxide laser as a tool for skin resurfacing. The carbon dioxide laser was first used by dermatologists in 1985 for treatment of actinic cheilitis, with encouraging results.8 In 1989, David et al8 presented a series of 21 patients treated with laser abrasion for fine facial rhytids. Histological study revealed marked improvement compared with untreated areas, with new stratum corneum formation, disappearance of solar elastosis, and formation of a new subepidermal band of compact collagen bundles. Changes were similar to those seen with phenol peel and dermabrasion.8 In 1996, Cotton et al1 studied the wounding depth of highenergy, short-pulse laser at increasing energy levels. At the highest energy level tested (2 passes at 400 J and 10 W), they measured a wounding depth of 0.14 to 0.25 mm, approaching the depth of a medium phenol peel. They noted a dermal collagen “repair zone” with increased fibrosis which has been recognized as the most clinically beneficial effect of CP or dermabrasion.

Until recently, efforts at laser skin resurfacing were hampered by cumbersome handpieces and small spot diameters. With the advent of small computer-controlled handpieces generating preprogrammed patterns of skin injury, large areas of the face can be abraded to a uniform depth in a relatively short period.

Efforts to compare laser skin resurfacing with CP have previously been possible only in retrospective analysis of patients treated with one or the other technique. Our study made a direct comparison between differently treated sides on the same individual. One difficulty in the present comparison is the expected difference in wounding depth between a laser and a deep CP. Prior histological studies have demonstrated a significantly shallower wounding depth with a laser (0.14- 0.25 mm)1 compared with a deep chemical peel (0.60-0.80 mm)3 However, both treatments are frequently recommended for patients with sun-damaged skin and fine rhytids, and both are considered comparable alternatives for the purpose of this study. Indeed, in our patients, the laser seemed to have a more pronounced effect in the thicker skin areas, despite histological evidence of shallower injury.

Accepted for publication June 27, 2000.

Presented at the Fall Meeting of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, San Francisco, Calif, September 1997. Reprints: PhillipR.Langsdon,MD, 7499 Poplar Pike, Germantown, TN 38138

(e-mail:[email protected]).

REFERENCES

1. Cotton J, Hood AF, Gonin R, Beesen WH, Hanke CW. Histological evaluation of preauricular and postauricular human skin after high-energy, shortpulse carbon dioxide laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132:425-428.

2. McCollough EG, Langsdon PR.Dermabrasion and Chemical Peel: A Guide for Facial Plastic Surgeons. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc; 1988:53-89.

3. Brody HJ.Chemical Peeling. St Louis, Mo: Mosby- Year Book; 1992:1-5.

4. Baker TJ. The ablation of rhytids by chemical means. J Fla Med Assoc. 1961;48:451-454.

5. Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Seckinger DL. A second look at chemical face peeling. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37:487-493

6. Tse Y, Ostad A, Lee HS, et al. A Clinical and histologic evaluation of two medium-depth peels: glycolic acid versus Jessner’s trichloroacetic acid. Dermatolog Surg. 1996;22:781-786.

7. McCollough EG, Hillman RA Jr. Chemical face peel. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1980;13:353-365.

8. David LM, Lask GP, Glassberg E, Jacoby R, Abergel RP. Laser abrasion for cosmetic and medical treatment of facial actinic damage. Cutis. 1989; 43:583-587.

(REPRINTED) ARCH OTOLARYNGOL HEAD NECK SURG/VOL 126, OCT 2000 WWW.ARCHOTO.COM 1199 ©2000